Is LoRa (Long Range) technology magic?

by Jon Adams N7UV

Is LoRa (Long Range) technology magic?

No, just good old fashioned math, signal processing, and silicon engineering know-how.

What makes LoRa so special? It's a modulation scheme that is fairly unusual in the natural world, save some animals and charged particles interacting with the Earth's magnetic field.

LoRa is a form of radio frequency modulation like AM, FM, SSB, CW, etc., but one that has some very impressive characteristics making it ideal for static high path loss situations. And it can provide this kind of performance while sipping microjoules from a 10-year-lifetime lithium primary battery or an inch-square solar panel and a supercap. LoRa is a radio transmission technique, not an end application!

LoRa is the trademarked term for a chirp spread spectrum (CSS) technology developed by semiconductor company Semtech headquartered in Southern California, USA. The silicon that Semtech manufactures is a complete radio transmitter/receiver on a chip. Chirp spread spectrum has been used by the military since World War II, it's nothing new, it just used to be really complex to implement in hardware. It's a form of frequency shift keying (FSK) where it's not the absolute frequency that encodes the information, but actually the rate of change of that radio frequency. That's what makes it novel and so remarkable.

Semtech developed LoRa for the Internet of Things (IoT) marketplace. For them, the IoT is communicating flow rates from a water meter that's in a concrete box mostly underground, a gas or electric meter on the side of a house, to a aggregator site on a phone pole a kilometer away. In fact, that and similar environments and uses are what has made LoRa radio technology so successful in the global marketplace. LoRa has discrete settings that allow a wide range of data rates, channel occupancy times, power consumption, and radio link budget. Every one of these settings might find value in a particular situation.

There's no fees to use it other than the cost of the semiconductor chip, which is a few dollars US. There are manufacturers all over the world that take Semtech chips and incorporate them into their products. Much of Semtech's LoRa business is in selling chips into devices that water, electric power, and gas utilities that need to communicate to their on-premises metering equipment. LoRa chips can be configured to consume extremely little power, and allow that meter's battery to last a decade. Due to the modulation method and receiver performance, 20-byte 1% packet error rate receiver sensitivities of -120 to -150 dBm are easily achievable. Compare that to a typical analog FM receiver breaking squelch at maybe -120 dBm and a usable signal needing to be around or greater than -110 to -105 dBm, and at those received power levels still often not able to meet the 1% packet error rates that LoRa does.

Semtech's chip technology is in its 4th generation now, and most of the silicon they make supports 150-960 MHz continuous; some of their chips also support 2400-2500 MHz, that's potentially interesting too. (Sadly, they don't support the 1240-1300 MHz 23 cm US ham band - that would be awesome if they did...)

LoRa, as implemented by Semtech, supports a wide range of data transmission rates from 11 bps (about that of a 20-word-per-minute Morse code operator) to 62.5 kbps. The challenge with very low data rates is that a message can tie up a channel for tens of seconds, cratering overall channel capacity. But the link margin is huge! However, completely satisfactory link margins can be had at LoRa settings that provide over-the-air data rates of nearly 8 kbps with channel occupancy times in the 40 ms range, vastly improving the channel availability.

Because of LoRa's strong ability to work far below the noise floor, carrier squelch multiple access (CSMA) for the purposes of collision avoidance (CA) doesn't exist in the LoRa world. However, it does have something nearly equivalent, channel activity detection (CAD). While Generation 1 LoRa chips had a limited CAD function, generation 2 and greater LoRa chips have a full-featured CAD that allows the transmitter to check the channel for activity before making the decision to transmit a LoRa packet. CAD produces an outcome similar to that of CSMA-CA. At the aforementioned "nearly 8 kbps", a CAD operation takes just 1.1 milliseconds. Academic papers have really begun to dig into ways to improve the overall channel availability through innovative ways of using CAD.

Hams started experimenting with LoRa around a decade ago, nearly all in Europe. There are lots of European academic papers on LoRa written since the mid-2010s, there are funny-hat-wearing Swiss hams on YouTube who talk about LoRa, there are whole ham clubs using LoRa for amateur radio comms and at least a few who are experimenting with new ideas to take greater advantage of what LoRa has to offer. All are terrific resources for learning more about LoRa and how hams can take best advantage of it.

European hams have different rules and regulations, and different radio frequency bands than most North Americans do, and especially US hams. Fortunately, in most parts of Europe and much of the rest of the world, most hams have common access to the 70 cm band, which means equipment availability is high.

Amateur Packet Reporting System (APRS)

APRS, as was envisioned by WB4APR, was and is an application to establish a highly robust tactical messaging system using amateur radio digital communications, which was growing quickly in popularity around 1980. His goal was to allow any suitably equipped ham to capture, in a short period of time, an overview of what was going on (from a ham radio point of view) in the local area, including announcements, bulletins, messages, alerts, weather, objects, events, frequencies in use, nets, meetings, hamfests, ham satellites in view, mobile/portable device locations, and to be able to map this activity. Messaging is a core part of APRS!

Many, including WB4APR, stated that APRS wasn't intended to be a vehicle/person tracking system, but indeed that is generally considered to be the most common use of APRS today. To a great extent, that use has taken away from the original intent of messaging and situational awareness. Back when APRS was first envisioned, the GPS constellations that we take for granted nowadays didn't exist, and once they became available the cost of a GPS receiver was astronomical (pun intended). Nonetheless, as GPS prices plummeted, it became easy to add GPS to a mobile setup. There's nothing wrong with tracking mobile/portable units, it's critical to remember that APRS is supposed to be an amateur radio situational awareness system, which also includes keeping track of things that are moving. Mike KC8OWL has been one of the leaders in reinvigorating the "messaging" aspect of APRS with his "APRS Thursday" program, encouraging APRS-equipped hams to send a message.

What does LoRa have to do with APRS? First, they're two different things. LoRa is an advanced, modern, wireless digital modulation technology, and APRS is an application (an "app") that relies upon some method of wide-area wireless communications.

Traditional APRS (like what is heard on 2 meters) uses a very mature (or nearly obsolete, to this writer) digital modulation technology called AFSK (audio frequency shift keying) that uses simple analog/digital modems (TNCs) to use the FM radios that continue to be the most common item the average ham has access to. It's straightforward to connect a TNC to a suitable 2 meter FM radio and, so long as the ham gets the wiring right, the audio levels properly set, and the RF path is solid, the TNC can generate a data packet and generate an audio waveform that modulates radio's microphone input, the radio transmits the packet, and the remote station (digi, igate, another operator, etc.) using a similar setup can receive, demodulate, and then read the contents of that data packet. Easy-peasy! (For AFSK APRS, please don't use VOX to key the transmitter!)

There are two major challenges with legacy amateur packet radio. First, AFSK modulation used over the air is very sensitive to distortion, FM capture effect, random noise bursts, slow and fast path fading, mobile fading, etc. The protocol selected to encode the information is AX.25, a variation on X.25, a protocol designed for wired packet-switched communications. X.25 works because it is on a wire, and and all units can detect whether the wire is busy or not, and there is a very low probability of external noise corrupting a bit. The A in AX.25 means "amateur", as the hams who worked with X.25 did a few tweaks to it, and christened it AX.25. Over a radio channel AX.25 is problematic. It's not designed for a real-life radio channel, with distortion, multipath, FM capture effect, random noise bursts, hidden transmitters, etc. AX.25 has no error correction capacity, so if a bit is corrupted over the radio channel, the receiving end has to throw out the entire packet, and that entire channel occupancy time has been wasted. Why was this selected? Because, back in the mid-1970's, it was available, understood, and was designed for packet-switched networks, so why not? And could be implemented on fairly inexpensive (even for the 1980s) hardware.

Today, AFSK is crude. It was very common back in the dial-up modem days (does anyone even remember those dulcet modem tones?), since all that there was available was an plain-old-telephone-service (POTS) audio circuit between two computers. AFSK was an easy way to encode digital information on a voice-grade telephone connection. The important thing about an old-school telephone circuit is that it is in effect a wire, not nearly as subject to the real world vagaries of a radio channel.

So here we hams are in the 2nd quarter of the 21st century, still using a set of technologies that are now about 50 years old. LoRa data communications represents a thousand-fold improvement on legacy FM AFSK!

Amateur packet radio on a simplex channel is constrained by many factors - over the air data rate, error detection and correction, channel capacity, hidden transmitters, interference, and received signal to noise ratio.

ALOHA

ALOHA! Not only is it the way to say "hello" and "goodbye" in Hawaiian, but it is also the name of a protocol that allows multiple devices to communicate over a shared channel. The protocol was developed (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ALOHAnet) at the University of Hawaii in the 1970s as a way for the university's computers on the different islands to transmit and receive data. Without getting into the math, a simplex unslotted ALOHA channel has a capacity of around 18%. Yes, there's a version of an ALOHA network that can work at up to 36% channel capacity, but it requires all the devices to be synchronized. Maybe we'll discuss that later!

A cool thing about ALOHA is that every device on the channel can potentially communicate with any other device on the channel. An even more cool thing is that if there's a message or data that everyone on the net needs to receive, the message doesn't need to be sent out to each end device individually, it can be broadcast to all. Sending to all devices doesn't take any more effort or channel time than to one device. Neat for situational awareness, where everyone needs to stay informed.

A challenge with ALOHA: think of that 18% value. That means that in a period of 1 minute / 60 seconds, the total channel availability is statistically about 11 seconds. That's not a lot of time. Now for the average ham radio installation, think of how long a packet takes to transmit using AFSK over a stock FM radio. A stock FM radio requires a certain amount of time to switch from receive to transmit, then a certain amount of time to switch from transmit back to receive. The RX to TX switching time is generally acknowledged by most manufacturers to be 250 milliseconds (ms). A typical compressed position packet sent to "APRS" via WIDE1-1,WIDE2-1 (the recommended path in most scenarios) is about 48 bytes long, and at 1200 baud takes 320 ms to send. Add those two together and the entire transmission time is 570 ms, about 5% of that 11 seconds that's available. A wx packet sent to "APRS" via the same route with the same TX delay takes up about a second, about 10% of the available 11 seconds. Beacons (especially informative yet wordy ones) can eat up more than a second of that 11 seconds. Messages (one of the original purposes of APRS) are spec'd to be 67 characters in length, which isn't much given that SMS messages 25 years ago were 140 and are basically limitless nowadays. A 67-byte message with the TX delay will take more than 900 ms to transmit. A 1200 baud APRS channel has very limited capacity!

With 1200 baud, how's a highly robust tactical messaging system to work? First, it's really important that every station on the air transmits only as often as is useful to others. For rapidly changing situations (an emergency, an event with a lot of moving things that need tracking, etc.) the channel is quickly overwhelmed, and if the hams are working with first responders and others with more functional networks, it's not looking good.

What to do, what to do? That 250 ms TX delay right there consumes over 2% of the 11 seconds available in that minute, and provides no information benefit. 250 ms is 2/3 of the on-air-time of a compressed position report! How about getting rid of the TX delay? Not with the existing analog FM radio technology. What about increasing the over-the-air data rate? Would require new TNCs, a completely different and much more complicated interface to a stock radio, and in fact may not be possible with most radios. And most hams aren't keen to hack into their radio and solder connections here and there. How about enforcing time slots? Remember that can double the amount of channel capacity from 18 to 36%? Well, that requires radios with knowledge of time down to milliseconds. What about compression? Squeeze the entire packet, including callsigns and everything, down using a lossless compression technique like zip or gif?

All of the above ideas are practical and even realizable right now! This is where LoRa APRS comes in. It's a completely modern, vastly more efficient method of encoding data for transmission over a shared radio channel. The RX to TX to RX time is a few microseconds each. The available data rates run from less than 200 bits per second to well over 50 kbps. Oh, and no radio hacking required! There are compression techniques that have been discussed but not (yet) implemented. And with every transceiver having the ability to have GPS attached, time slotting can be a solid move forward.

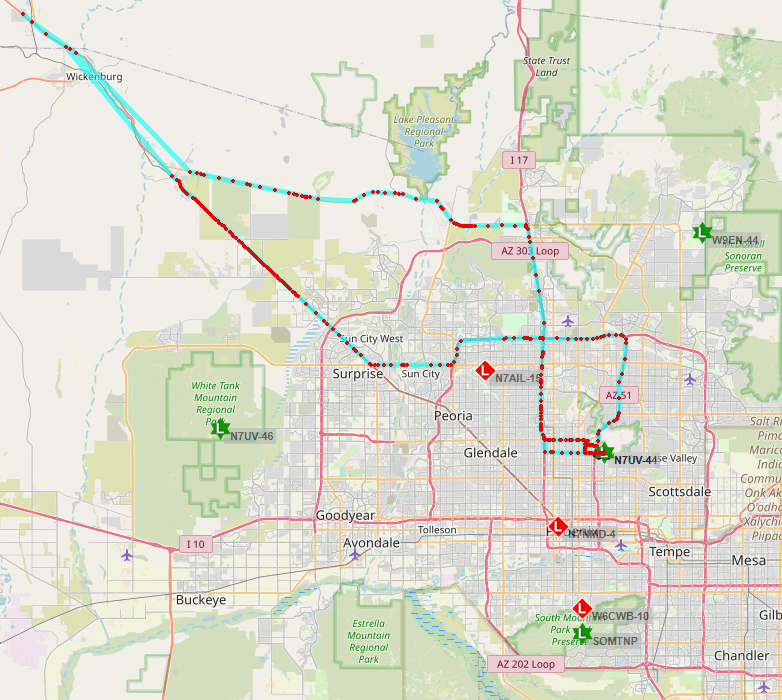

Here's a screen grab from aprs.fi of my N7UV-4 LoRa mobile last week when I went on a trip to Death Valley and back. Obviously, once I got away from the infrastructure here in the valley, there wasn't any coverage. But what pleasantly shocked me was the range performance to the NW side of Phoenix. Those few position locations NW of Wickenburg are nearly 60 miles away, and skirting the ground for a lot of that. Wickenburg itself is mostly in a river valley so I don't expect coverage there.